What I (Really) Write About When I Write About Murder

by Tina deBellegarde

I write a mystery series set in the fictitious town of Batavia-on-Hudson. Ostensibly I am writing about murder, but in reality, I am writing about the villagers. The murder, the investigation, the red herrings, the mis-direction are all there to unearth the motivations, the fears, the aspirations and the growth of my characters.

When I say motivation, I don’t mean motivation for murder, but motivations of other types. Why we lie, why we love, why we hate. Why we join a group or stay on the outside. Why we include some and exclude others. A small town is a wonderful petri dish. I live in a village similar to Batavia-on-Hudson. My heroine, Bianca St. Denis, is an out-of-towner, much like I am, and is perfectly poised as an observer. Being from the outside gives her fresh eyes to see what the locals may not have enough distance to recognize or willingness to admit.

I have always preferred character-driven stories as a reader. I want my reading to be entertaining, but I also want it to be thought-provoking. I am happy to work out my issues by seeing them reflected in a character on the page. Engaging fiction can give us a good story and a great deal to think about at the same time. I aspire to do that with my books and stories. I think many readers are also happy to investigate their emotions in the midst of being entertained.

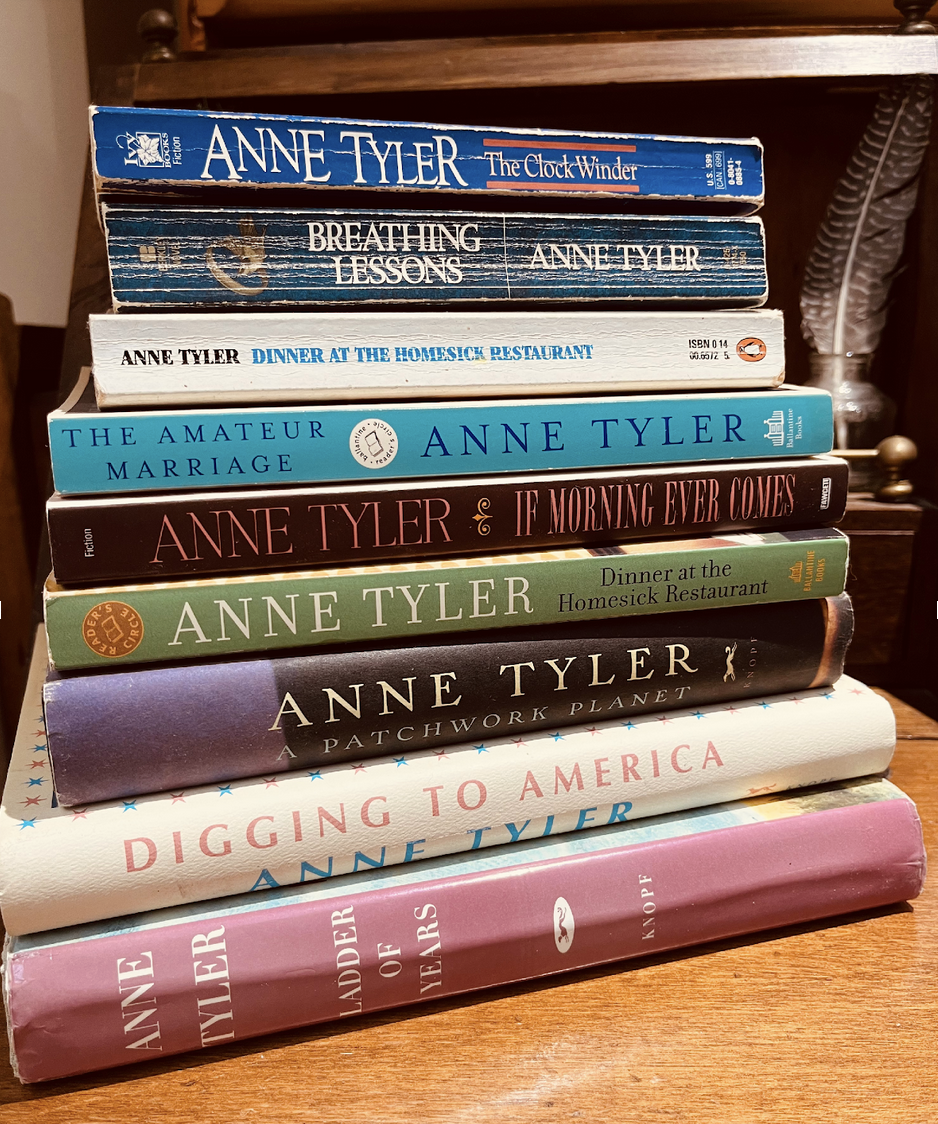

The author I consider the best observer of people is Anne Tyler. Her books are gentle and mundane, yet she demonstrates that stories about ordinary people living ordinary lives can prove to be extraordinary. I have always used Anne Tyler as my guide on how to write people. Many of her characters are quirky, but that is not her stepping out of reality; she’s reflecting it. People are more eccentric than we admit because we are used to them. We accept their oddities because they are beloved. We learn to love Tyler’s characters as well. When I dig into a book, I want to love the characters. I want to care and when I care, I can suspend disbelief and be completely immersed in the story.

The murder mystery in my books is the device I use to move a plot forward, but what is really happening is that characters are living their normal lives, showing us who they really are. The murder and the investigation are excuses to insert ourselves in the lives of the villagers, to watch them interact and deal with their everyday challenges, and work out their past traumas.

What I love about writing a murder mystery is that it emphasizes and exaggerates personalities. Fearful characters are more fearful, suspicious characters, problem-solvers, etc. are all distilled to their essence. It is an efficient way to get to understand the nature of a person quickly.

Early in my writing when I asked other authors for feedback on my first manuscript I was told that I should decide whether my book was a mystery or women’s fiction. I understood this but I was also a bit baffled by it. I believe that we can do both in our writing. The evolution of my main character and a few of my tangential characters seems like a reasonable goal in a story. I enjoy reading and writing the puzzle of a mystery, but I enjoy even more the existential concerns of the characters.

As my characters navigate real-life challenges, as they demonstrate the courage it takes to live an ordinary life, I feel empowered. Sometimes, I think we forget just how brave we are when we confront our everyday obstacles. We underestimate ourselves and those around us. When in reality we are all putting one foot in front of the other each day and overcoming. Fiction characters are a safe way for us to investigate just how much we are tested on a regular basis. How we should be proud of our daily achievements. How we rise above betrayal and deception. How we handle all that life throws at us.

When Bianca, my amateur sleuth, decides to insert herself into an investigation, she is usually doing so to help someone else. She is not just curious and nosey, but brave and accomplished. She is showing us how determination and devotion can tackle even the biggest of obstacles.

When I write about murder, it is just an excuse to witness in three hundred pages how a community functions and supports each other. When the villagers start to heal and they band around my protagonist, they are learning to live with the new normal. They all know that the world is not what it was before. The mystery may be resolved, but the world has shifted. It is this shift that I am most interested in.

This essay originally appeared in Karen Odden’s December 2022 newsletter here. Visit Karen’s website for great content on historical mysteries.

Header photo by Ben Lambert on Unsplash others courtesy of Tina deBellegarde